Borges Invented the Internet

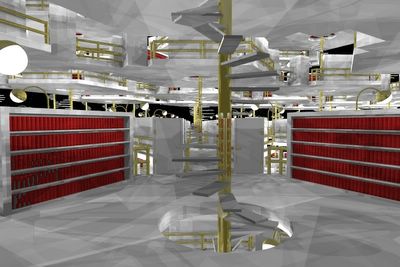

Picture from: http://jubal.westnet.com/hyperdiscordia/library_of_babel.html

I wandered down Calle Florida to the café where I was supposed to meet Lorenzo for a quick afternoon bite and an introductory tour of the city. Given that it was my first day in Buenos Aires, I was happy to have a friend of the family as a contact here but also somewhat eager to explore on my own. I walked past the tourist shops selling the mate gourds the gauchos use for drinking their famous beverage of choice, past the music stores spilling the sounds of the tango out onto the street, past the many enterprising young dancers using these sidewalk stages to perform for pesos. I looked down the alleys and streets that forked off in every direction and couldn’t imagine how much time I would need to explore all of this city.

Lorenzo was waiting for me dressed in pants and a sweater vest despite the sweltering heat outside. He sipped his café con leche and looked as if he were contemplating the mysteries of the universe. “What are you most interested in about Buenos Aires?” he asked. Everything, I thought. But was able to explain that, academically, at least, I was interested in the way technology here was influencing culture and society. He asked me if I had read Borges and I embarrassedly replied that I hadn’t. “You must,” he chuckled, “you know - he invented the internet. Come on, lets go to another café.” He led me a few blocks away to Café Tortoni. “Borges used to come here all the time,” he said. “You like coffee?” For the next half hour or so he tried to explain how this greatest of Argentine writers had been both a clairvoyant able to see into the future and past as clearly as if it were the present, and a prescient technophile who foresaw the entire internet revolution. Incredulous but intrigued, I looked forward to having a chance to read the work of this purported sorcerer.

The Garden of Forking Paths

In the collection of eight short stories called “The Garden of the Forking Paths,” Borges presents a dazzling array of fantastical tales. The stories include the title piece as well as seven other self-described “tales of fantasy.” Though smugly stating in his forward that the stories need no explanation, Borges prepares the reader somewhat for the journey when introducing “The Lottery of Babylon” by his tongue-in-cheek admission that it “is not wholly innocent of symbolism.” This understatement is only the beginning of a series of amazing commentaries that left me feeling that Borges not only invented the internet but perhaps had some role in chaos theory and relativity as well. His stories bend time and logic, forcing the reader to abandon traditional linear reading patterns and accept that the ride he is taking us on is purposefully neither cohesive nor sequential. Like the mirrors he places before his characters, his stories seem to create real images that only upon closer inspection reveal their need to be viewed as representations of something else or somehow deconstructed so as to decipher their meaning.

The piece that may have the most obvious relevance to modern technology and the internet is the “Library of Babel.” By hypothesizing an endless library of infinite space that contains all books, Borges sounds remarkably similar to technophiles that wax poetic about the concept of the internet. This unbounded space dedicated to the collection of all knowledge, he muses, must be the handiwork of a god. Borges does not merely present the Library as a positive vision, however. His Library is an immense labyrinth containing all possible permutations of text, whether true, false or simply nonsensical. Likewise, any user of the internet has likely also felt that “for every rational line or forthright statement there are leagues of senseless cacophony, verbal nonsense, and incoherency.” (pg. 114)

Borges further claims that the Library is infinite and that those who imagine that there are limits and that there must be an end somewhere are “absurd.” (pg. 118) This notion of infinite knowledge and resources pervades commentary about the internet and a similar sentiment to Borges can be found in numerous joke websites that have been made that inform the user that he or she has “reached the end of the internet” and must now go back. An example can be seen at: http://www.internetlastpage.com/. In the footnote following the text, Borges comments that the infinite nature of the library need not be thought of strictly in terms of size. By hypothesizing a single book with infinitely thin pages, Borges seems to have predicted the current wave of technological innovation focusing not on expanding bandwidth but rather using existing bandwidth more efficiently by subdividing and maximizing space.

Even the social effects of the Library are remarkably predictive. Like the unbounded joy that all men felt when the Library was announced, the arrival of the internet brought a bubble of optimism and a feeling of endless potential. I felt like Borges was describing Silicon Valley in the late 90’s when he remarked that “[a]ll men felt themselves the possessors of an intact and secret treasure. There was no personal problem, no world problem, whose eloquent solution did not exist – somewhere in some hexagon.” (pg. 115) After an initial delirium where men rushed about trying to unlock the secrets of the universe in the Library, as in the internet bubble, “[t]hat unbridled hopefulness was succeeded, naturally enough, by a similarly disproportionate depression.” (pg. 116) Even his comments on the superstitious belief in the “book-man” can be analogized to the holy grail of artificial intelligence that has long captivated the cyber world.

Perhaps spurred on by Borges’ vision, there have been numerous attempts, many ongoing, to create an internet-based library of books to rival the Library of Babel. In 1995, the US government funded and helped launch the Digital Library Initiative (DLI), a $25 million dollar project to create a pan-cyber library. The Library of Congress, as well, has pushed a National Digital Library (NDL) program with the vision of putting its entire vast collection on line. These attempts, while ambitious, would still of course not equal the infinite expanse of the Library of Babel, but it seems to be a conscious move in that direction. With many predicting a hundred million-fold growth of information on the internet in the next century, we may see something very close to Borges’ Library coming soon to a laptop near you. What will be the effect of this incredible growth of readily accessible knowledge? Will it lead to a blossoming of education and information used for good ends, or will the endless expanse tend to drive people insane and lead to only more disagreements and squabbling as it did in the Library of Babel?

Fascinated by these similarities, I searched the internet and found several other interesting comparisons. As it turns out, Lorenzo was not the first commentator to compare Borges works to internet technology. The “infinite stories, infinitely branching” presented in the invented Herbert Quain book, “April March” were in one article seen as direct predecessors to the HTML links used to lead internet users to endless other pages. In a choose-your-own-adventure environment, no two experiences are alike. Another likened the predicament of sorting out which of a bewildering array of possible paths Steven Albert faces in “The Garden of the Forking Paths” to the task of routers, gateways and packets and the amazingly sophisticated logic that must be used to move information between nodes on the internet. A third likened Borges’ virtual world of “Tlon” to cyberspace and virtual reality, and their increasing grip on the minds and imaginations of normal people.

Most commentary analogizing Borges’ writing to the internet seems to take a positive stance. Celebrating the amazing technology of the internet and deifying Borges for predicting it seems to miss the point. Borges presents a fantastic tale ripe with foresight, but also a clear warning about the dangers this technology will bring. Besides the insanity that an endless supply of knowledge will bring, Borges alerts us to the danger of blind worship of technology as well by the claim that “young people prostrate themselves before books and like savages kiss their pages, though they cannot read a letter.” (pg. 118) Borges goes as far as to surmise that the effects of the Library may drive the human species to extinction, while the Library endures. This warning rings of the sci-fi tales where computers and machines take control and eventually kill the humans off. Similarly in “Tlon, Uqbar, Orbis Terius,” the virtual world created by men eventually overtakes the real world and erodes peoples ability to tell real from imaginary. Borges seems to offer hope as well, however. He reminds us that this virtual world we are getting lost in is “the rigor of chess masters, not of angels.” He ends “The Library of Babylon” with a the “elegant hope” that humans will understand that there is an order to the endlessness and not subjugate humanity in the fascination with the seemingly infinite promise of the Library. Likewise, we should remember that while the internet and modern communications technologies have wondrous potential, we must keep an eye on humanity and never let our desire to modernize blind us to the harmful effects of that modernization.

If the Internet is a Latin American Creation, Why is it not a Latin American Phenomenon?

Had Borges invented the Internet, he would probably be disappointed by the role it is playing in his home region of Latin America. At the turn of this century, only 1.5 percent of Latin Americans used the Internet – a number composing only 3.2 percent of the worlds users. Part of this is due to the dominance of English language sites on the web. Only one or two percent of all web content is in Spanish, while over 70 percent is in English. These figures are changing rapidly but does still not reflect the fact that more non-native than native English speakers are now online.

Furthermore, internet usage patterns differ between Latin Americans and their North American counterparts. While e-commerce is already having a significant effect in the overall North American economy, it has largely failed to achieve traction in Latin America. This is due somewhat to the fact that many users in Latin America use shared or public computers – because they are not at home, they are less likely to participate in auctions that require repeated checking over time, and less likely to realize any convenience value from “shopping from home.” The consumer patterns will change as more homes get wired, and is already becoming a significant business to business phenomenon. The one area where there may be hope is in promoting shared computers in schools for education. While homes will be slow to adopt, if attention can be directed towards wiring schools, many young people will be able to benefit from the positive aspects (and maybe avoid some of the negative or worthless uses.)

The largest barriers to Latin American use are the costs of machinery and connections. These costs are relatively much higher in Latin America, where communications infrastructure is lacking and there are few local tech manufacturers. Most households are still too poor to have a computer. While public and shared computers are great for email and recreation, they are less likely to become a permanent fixture providing education, or information on daily needs such as health advice. The high costs ensure that the small percentage that is able to get computers and get online are the ones that are already rich. With gaps between rich and poor already alarmingly large, this added distancing should cause some distress. The reliance on foreign aid to acquire and install new technologies leverages developing economies and endangers their stability.

While internet usage is increasing rapidly in Latin America, the patterns of usage are problematic. Regional governments should pay careful attention to make sure that the beneficial aspects of the internet are promoted and available to all. The Library of Babel should not be open only to the richest segments of society (those who least need the opportunities it would present) but to everyone. If new technologies only widen the existing gaps between rich and poor, they may not be the answer. Governments should also not allow themselves to be pressured by outside forces to adopt and promote technologies at the expense of other more pressing needs. Technology is a powerful tool, but it is just a tool, not a solution in itself.

So Did Borges Invent the Internet?

While Lorenzo’s claim that Borges invented the internet may initially be as laughable as Al Gore’s claim, the foresight is remarkable. Like many inventors, Borges would probably have grave concerns over the effects of their inventions on society. He would likely be deeply worried about widening quality of life gaps in the developing world and the role technology may be playing in widening them. If he knew what people were using the Library for, Borges would probably be turning in his grave. Nevertheless, we should remember that despite all the analogies and similarities we can draw, Borges writings have more to do with the social and philosophical implications of technology than they do with any actual insight into how to create technology. Not only was Borges writing before the technical sophistication existed to make the modern internet, he offers no instructions on how his self proclaimed fantasies could actually be created in the real world.

But perhaps Lorenzo was right. Those who claim that Borges’ stories were written well before the technology was developed to make the internet possible may be clutching to a linear and distractingly sequential vision of time. And like Borges explains nicely, the answer to a riddle is the one word that cannot be directly used. While the surface mystery in the “Garden of the Forking Paths” led us to the clever solution using the name “Albert,” Borges gives us this directly. We can only be left wondering if there is some further riddle to be uncovered, some key word he left out. I suppose I would not be surprised to see Borges smirk if we could resurrect him and ask, with all the similarities and analogies, why didn’t he just come out and say … Internet…?

2 Comments:

As we read this, books are being converted to digital form and being put on line at what we might call a blinding speed. As the dream of a universal digital library marches forward, there are plenty of reasons to be positive about this development. Never before has so much knowledge been so readily available. But what about those segments of society with disabilities we might ask? Is there no place for the blind in the Library? Not so, says one not-for-profit technology company from Silicon Valley. Benetech’s Bookshare.org is an online community that enables members of the blind, visually impaired and reading disabled community to legally share scanned books. This is an effort that Borges himself would likely have considered near and dear.

In 1955 Borges was appointed as director of the National Library in Buenos Aires. This was the job of his dreams and would seem a just reward for his contributions to Argentine literature. Ironically, however Borges's eyesight had been failing since childhood, and by then he was almost completely blind. "I speak of God's splendid irony," he wrote, "in granting me at one time 800,000 books and darkness." With all of Borges’ caution towards technology, the efforts of Benetech would likely provide the writer with just a little more “elegant hope.” Benetech has recently passed the 20,000 book milestone. While now only about five percent of books are available in an accessible format, this number is skyrocketing. Perhaps someday Bookshare will be able to count the 800,000 held by the National Library in Buenos Aires. Recently, Who knows, perhaps the potential is endless and one day we will have an all-audio Library of Babel accessible for free to those with disabilities.

Read more about Benetech and Bookshare.org here:

http://www.benetech.org/projects/bookshare.shtml

An interesting look at the genius of Borges and the current advances of technology in Latin America.

It prompted me to search the question of just who did invent the internet. I knew it wasn't Al Gore and he never made that claim. He said, that he "Took initiative in creating the internet".

In my search, I came across a book by Tim Berners-Lee; "Weaving the Web, The Original Design and Ultimate Destiny of the World Wide Web by its Inventor", it examines the Web as a force for social change and creativity. Gotta be worth consideration.

Until I find a better answer, I am going with the default; inventor of everything, Leonardo da Vinci. When you come to the end of the internet, he'll be there.

Post a Comment

<< Home